In this deep dive, we’re going to peel back the layers of Kafka and understand it from every angle—what it is, why teams reach for it, when it’s the right tool for the job, and how it actually works under the hood. We’ll take a question-and-answer approach so the concepts click faster and stay with you longer. Think of it as both a guided tour of Kafka and a quick reference you can revisit before your next interview.

Imagine Kafka as a nationwide postal service, but instead of letters and parcels, it moves streams of data. Producers are the senders, dropping their messages into topic “mailboxes,” which are further divided into neatly ordered trays called partitions. The Kafka cluster acts like a network of post offices, storing, routing, and making sure every message arrives where it should. On the other side, consumers are the recipients, collecting their messages at their own pace. And just like teams of mail sorters working together, consumer groups divide up the workload without ever duplicating deliveries. In essence, Kafka is a highly efficient, fault-tolerant postal system for data in motion.

What makes Kafka special? #

- High throughput, low latency → can handle millions of records/messages per second.

- Durable storage, Replayability → records persist on disk; consumers can re-read. You can rewind to past events, it retains data for a configurable period.

- Decoupling of systems → producers and consumers don’t need to know about each other.

- Horizontal scalability → just add more brokers/partitions.

Basic Terminology and Architecture #

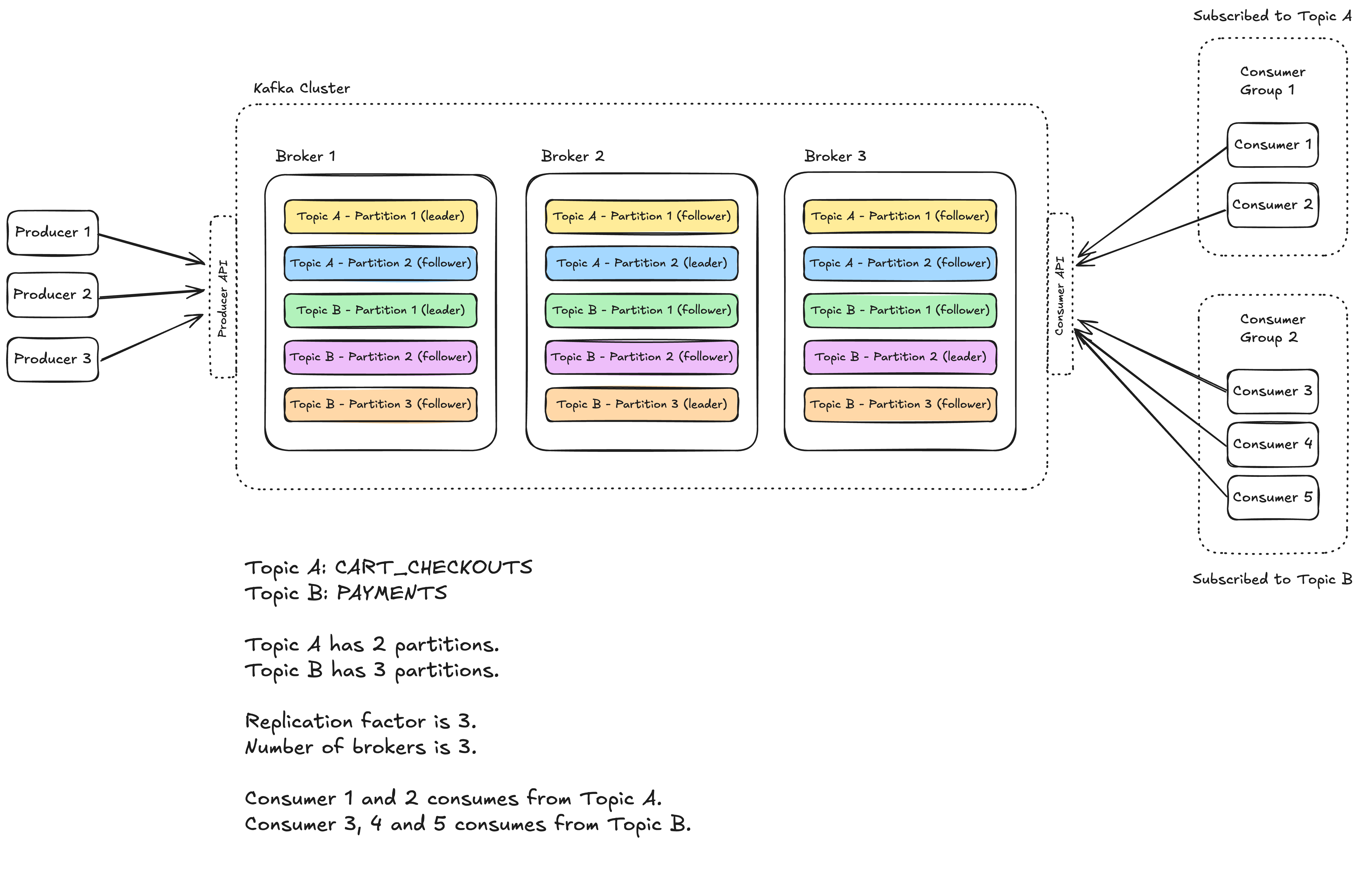

A Kafka cluster is made up of multiple brokers. These are just individual servers (they can be physical or virtual). Each broker is responsible for storing data and serving clients. The more brokers you have, the more data you can store and the more clients you can serve.

Each broker has a number of partitions, physical grouping of records. Each partition is an ordered, immutable sequence of records that is continually appended to – think of like a log file. Partitions are the way Kafka scales as they allow for records to be consumed in parallel. Partitions are further divided into smaller blocks called segments which store the topic data on the physical disk.

A segment is a physical file on disk that stores a portion of a partition’s data. Each segment consists of a .log file (actual records), .index file (maps offsets to file positions) and .timeindex file (maps timestamps to offsets). Read more about Kafka storage internals here.

A topic is just a logical grouping of partitions. Topics are the way you publish and subscribe to data in Kafka. When you publish a record, you publish it to a topic, and when you consume a record, you consume it from a topic. Topics are always multi-producer; that is, a topic can have zero, one, or many producers that write data to it.

Last up we have our producers and consumers. Producers are the ones who write data to topics, and consumers are the ones who pull data from topics. While Kafka exposes a simple API for both producers and consumers, the creation and processing of records is on you, the developer. Kafka doesn’t care what the data is, it just stores and serves it.

From a high-level point of view, there are two layers in the Kafka architecture: the compute layer and the storage layer. The compute layer, or the processing layer, allows various applications to communicate with Kafka brokers via API. The storage layer is composed of Kafka brokers.

Since Kafka brokers are deployed in a cluster mode, there are two necessary components to manage the nodes: the control plane and the data plane. The control plane manages the metadata of the Kafka cluster. It used to be Zookeeper (maintaining another system overhead gone) that managed the controllers: one broker was picked as the controller. Now Kafka uses a new module called KRaft to implement the control plane. A few brokers are selected to be the controllers. The data plane handles the data replication. Followers issue FetchRequest with offsets to the leader broker to get new records.

What do you mean by a Kafka Record? #

A record (formerly messages) is the smallest unit of data in Kafka. It’s what a producer sends, a broker stores, and a consumer reads. At a high level, each record is part of a Record Batch, and that batch is part of a partition log segment.

Logical structure of a record

| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Key | bytes (nullable) | Used for partitioning & log compaction |

| Value | bytes (nullable) | The actual payload |

| Headers | list<key, value> | Optional metadata (e.g., correlation-id) |

| Timestamp | long | Event time or log append time |

| Offset | long | Sequential ID within the partition |

| Checksum (CRC) | int | Data integrity verification |

| Attributes | byte flags | Compression type, timestamp type, etc. |

What is the underlying network protocol used by Kafka? #

Kafka uses a custom binary protocol over long-lived persistent TCP connections to brokers. That means it sends records in binary format over TCP. Binary encoding makes the record size smaller, less time is spent on processing (serialization/deserialization overhead) and lower bandwidth usage. Connection setup overhead happens once per broker, the connection stays open enabling batched writes and async I/O, resulting in high throughput and low latency.

How do we achieve parallelism in Kafka? #

Kafka’s parallelism comes from partitions, as each topic is divided into partitions that producers write to and consumers read from concurrently. The number of partitions defines your maximum parallelism — too few limits throughput, too many adds metadata overhead. Within a consumer group, each consumer is assigned one or more partitions, and no two consumers share the same partition, preventing duplicate processing. Ideally, the number of consumers should match the number of partitions: fewer consumers reduce parallelism, while extra consumers remain idle. In short, balance your partition count and consumer group size to maximize parallelism without unnecessary overhead.

Kafka’s log-centric design #

Kafka’s storage engine is a write-ahead log. Every topic partition is an append-only log file, where records are written sequentially with an offset. This design makes Kafka extremely fast because sequential disk writes are efficient, and it provides durability since records are persisted before acknowledgment. Once written, records cannot be altered. This immutability avoids consistency issues and increases reliability. The WAL also allows replay — consumers can re-read from any offset. Logs are segmented, and retention policies decide whether old data is deleted or compacted. This log-centric design is what differentiates Kafka from traditional queues and databases.

How is log compaction different from time-based retention? #

In Kafka, time-based retention deletes records once they’re older than a configured duration or once the log exceeds a certain size. That’s good for event streams where you only care about recent history. Log compaction, on the other hand, guarantees that Kafka keeps at least the latest record for each key, regardless of age. This is ideal when you want Kafka to act as a source of truth for state — for example, keeping the latest user profile or account balance. In short: retention keeps data by time/size, compaction keeps the latest value per key.

What do you mean by replication factor? #

It is the number of copies of each partition that Kafka maintains across different brokers in a cluster.

Example: If a topic has 3 partitions and a replication factor of 3, then:

- Each partition has 3 replicas (leader + followers).

- Kafka stores them on different brokers (to survive broker failures).

- Total =

3 partitions × 3 replicas = 9 partition replicasin the cluster.

If replication factor is 1, then we have only one replica which is our leader by default.

When should we use one vs many producers? #

Number of producers is not limited by the number of topics or partitions.

- One producer → multiple topics

- Simpler, fewer network connections, efficient batching.

- Common pattern when the same app generates different categories of events.

- Multiple producers

- Useful if you want different configs (e.g., different serializers, acks, retries).

- Sometimes chosen for isolation between pipelines.

Let’s talk about producer retries and idempotence #

When a producer sends record to a broker, the send may fail. The producer may retry sending it again.

This behavior is controlled by the retries (or in newer Kafka versions, delivery.timeout.ms + request.timeout.ms) config.

Retries can cause duplicates because the producer may not receive an acknowledgment even if the broker already stored the record. We can enable idempotence for the producer via config.

With idempotence (enable.idempotence=true):

- Each producer session is assigned a Producer ID (PID).

- Each record carries a sequence number.

- Broker deduplicates by rejecting records with the same PID + sequence number → ensuring no duplicates, even if retries occur.

You might have heard about “acks”. What are they? #

- It tells the producer how many acknowledgments it must receive from the Kafka cluster before considering a message “successfully sent.”

- This controls the balance between latency, throughput, durability, and consistency.

- This takes care of the producer-side delivery semantics/guarantees.

-

acks=0→ Fire and Forget- Producer doesn’t wait for any broker acknowledgment.

- Record is sent over the network and considered “delivered.”

- If the broker crashes before persisting, the record is lost.

- At most once.

- ✅ Lowest latency, highest throughput.

- ❌ No guarantee of durability or delivery.

- Use case: Logging, metrics, or telemetry where losing data is acceptable.

-

acks=1→ Leader Acknowledgment- Producer gets ACK once the leader broker writes the record to its local log (not necessarily replicated yet).

- If the leader crashes after ack but before replicas sync, the record is lost.

- At least once, possible duplicates if retry.

- ✅ Reasonable durability with good latency.

- ❌ Possible data loss if leader crashes before replication.

- Use case: Common default for applications where some data loss is tolerable.

-

acks=all(oracks=-1) → All In-Sync Replicas Acknowledge- Producer gets ACK only after the leader and all in-sync replicas (ISRs) confirm the write.

- Guarantees that the record won’t be lost as long as ≥1 replica remains alive.

- Stronger at least once guarantee.

- ✅ Strongest durability guarantee.

- ❌ Higher latency (must wait for multiple brokers).

- Use case: Financial transactions, orders, payments — where no record loss is acceptable.

Why do we need consumer groups? #

A consumer group is a set of consumers that coordinate together to read from a topic, such that:

- Each partition of the topic is consumed by only one consumer in the group.

- But multiple consumers in the group can work in parallel across partitions.

If consumers subscribe independently:

- Each consumer gets the full topic → duplicate processing.

- No parallelism benefit → every consumer does all the work.

- Failover is manual.

Consumer groups solve this with partition assignment and rebalancing while ensuring no duplicate reads within the group.

What are consumer offsets? #

- Each partition in Kafka is an append-only log of records.

- Every record inside a partition has a unique offset (0, 1, 2, …).

- A consumer offset = the position of the last record a consumer has processed in that partition.

Offsets let consumers:

- Resume after failure (don’t reread from the beginning).

- Track progress per partition (because consumers can read multiple partitions).

- Enable parallelism (each consumer in a group keeps its own bookmarks).

How are consumer offsets maintained? #

- Automatically by Kafka (default)

- Consumers commit offsets to an internal Kafka topic:

__consumer_offsets. - Stored as a compacted log keyed by

(consumer_group, topic, partition). - On restart, the consumer group coordinator fetches the last committed offsets from there.

- Manual commit by application

- You can control when offsets are committed (after successful processing).

- APIs:

commitSync()(synchronous, safe but slower).commitAsync()(faster but riskier if crash happens).

Let’s also discuss the consumer-side delivery semantics #

Controlled by when offsets are committed (manually or automatically):

| Commit Timing | Behavior | Semantic |

|---|---|---|

| Commit before processing | If crash → message lost | At most once |

| Commit after processing | If crash → message reprocessed | At least once |

| Use transactional consumer (EOS) | Processing + commit are atomic | Exactly once |

When do we need idempotent consumers? #

The default delivery semantic in Kafka is at-least-once where offsets are committed after processing. Now there can be cases when the consumer crashes just after processing but before committing the offset. In such a situation, another consumer can again consume and process the same record. Idempotent consumers can help in such a situation.

What are the strategies for building idempotent consumers? #

- Idempotent Writes via Primary Keys

- Store results in a DB where each record has a natural unique key (

txn_id,order_id,payment_id). - Use upserts (insert-or-update) instead of blind inserts.

INSERT INTO payments (txn_id, amount, status)

VALUES ('abc123', 100, 'FAILED')

ON CONFLICT (txn_id) DO UPDATE

SET status = EXCLUDED.status;

- If the same record is processed again → no duplicate row.

- Deduplication Log / Cache

- Keep a table (or Redis set) of already-processed record IDs.

- Before processing, check if ID exists.

- If yes → skip. If no → process and record ID.

- Trade-off: needs storage + lookup overhead.

How do we achieve Exactly-Once Semantics? #

- Writing messages with transaction IDs (transactional producer at work)

- Atomically processing messages + committing offsets (transactional consumers)

- Ensuring retries don’t cause duplicates (idempotency)

This provides exactly-once between producer → broker → consumer.

How can we handle hot partitions? #

A hot partition is the one that receives significantly more traffic than the others.

Strategies to avoid them

| Strategy | How It Works | Advantages | Trade-offs / Drawbacks | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Random Partitioning (No Key) | Don’t specify a key when producing; Kafka’s default partitioner distributes messages round-robin among partitions. | - Even data distribution - Simple to implement |

- No message ordering - Harder to group related messages |

High-throughput, stateless streams (e.g., logs, metrics) |

| 2. Random Salting of Key | Add a random suffix/prefix (e.g., salt = 0–9) to key to create multiple subkeys per entity. | - Spreads load of hot keys - Reduces skew |

- Complicates aggregation (need to “de-salt” later) - Increases key diversity artificially |

High-volume event streams with few dominant keys (ads, users, sessions) |

| 3. Compound Keys | Use multiple fields (e.g., adId + region, userId + deviceType) to form the key. |

- More even load distribution - Partial ordering preserved per compound key |

- Harder consumer logic if grouping only by one part of the key | Entity-based data with multiple independent dimensions |

| 4. Custom Partitioner | Implement a partitioner that uses custom logic (e.g., adaptive hashing, weighted distribution). | - Full control over partition routing - Can handle domain-specific skew |

- Requires custom code - Harder to maintain |

Domain-specific workloads where built-in partitioner isn’t optimal |

| 5. Back Pressure / Rate Limiting | Producers slow down when lag or broker pressure rises; manages throughput dynamically. | - Prevents cluster overload - Easy to implement |

- Doesn’t fix imbalance - Reduces overall throughput |

Managed Kafka clusters or self-hosted clusters under burst load |

What are the different partitioning strategies? #

| Strategy | Ordering | Load Balance | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key-Based | Per key | Depends on key distribution | Entity-based events (user, order) |

| Round-Robin | None | Perfect | Logs, metrics, analytics |

| Sticky (No Key) | None | Good (batched) | High-throughput ingestion |

| Custom | Optional | Excellent (if designed well) | Domain-specific partitioning |

| Manual | You control | Manual balance | System-level routing |

| Composite Key | Partial (by composite) | Better than single key | Multi-dimensional data |

| Time/Salting | None (for base key) | Excellent | Avoid hot partitions |

When is message ordering important? #

Kafka only guarantees ordering within a single partition, not across partitions. That’s a core rule.

Let’s say you produce these two events:

User123 -> "Account Created"

User123 -> "Account Deleted"

With round-robin partitioning:

“Account Created” → Partition 0

“Account Deleted” → Partition 1

Consumers reading partitions independently might see: “Deleted” before “Created”. That breaks the logical timeline of events.

One way of solving this is by using key-based partitioning. We can use the userId as our key so that Kafka’s partitioner send records for the same user id to the same partition every time.

partition = hash("user123") % num_partitions

What is rebalancing? #

Rebalancing is the process where Kafka redistributes partitions among the consumers in a consumer group.

- A consumer group = multiple consumers working together on the same topic.

- Each partition can only be owned by one consumer in the group at a time.

- When the group membership changes (a consumer joins, leaves, or crashes), Kafka reassigns partitions → that’s a rebalance.

It’s like reshuffling tasks among workers when someone joins or leaves the team.

When does rebalancing happen? #

- Consumer joins

- A new consumer subscribes to the group → Kafka assigns it some partitions.

- Consumer leaves/crashes

- A consumer shuts down, crashes, or is kicked out due to heartbeat timeout → its partitions are reassigned to remaining consumers.

- Topic partitions change

- Admin increases partitions in a topic → Kafka must redistribute them across consumers.

- Subscription changes

- A consumer subscribes to a new topic or changes its subscription → group must reshuffle assignments.

Who manages rebalancing? #

- The Group Coordinator (a special broker) orchestrates rebalancing.

- Consumers use the Group Protocol (via heartbeats) to agree on who gets which partition.

What happens during a rebalance? #

- All consumers in the group stop fetching records.

- The group coordinator pauses consumption and figures out a new partition assignment.

- Each consumer gets its new assignment.

- Consumers resume fetching from their new partitions (using stored offsets).

Why is rebalancing both good and bad? #

✅ Good:

- Ensures fault tolerance (if a consumer dies, others pick up its work).

- Allows horizontal scaling (add more consumers → load spreads out).

❌ Bad:

- During a rebalance, no consumer in the group processes records → pause in consumption.

- Frequent rebalances can hurt performance (thrashing).

How Kafka mitigates frequent rebalancing #

- Heartbeat & session timeouts: Avoid kicking consumers out too aggressively.

- Incremental rebalancing (KIP-429): Instead of stopping all consumers, only adjust the ones impacted.

- Sticky partition assignment: Try to keep the same consumer-partition mapping as much as possible, to reduce churn.